New York City’s Fifth Avenue has been shorthand for glamour and wealth since the 1800s, but the boulevard began with far less fanfare. When it was first cut through upper Manhattan, it carried the plain name “Middle Road,” running across a broad, largely undeveloped tract. That land—sold in 1785 to help raise municipal funds for the young nation—would later become the center of New York’s most rarefied social world. As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth and the Gilded Age came into view, the 1811 Commissioners’ Plan formalized the street’s new identity, renaming Middle Road as Fifth Avenue.

With the city’s growth pushing steadily north, America’s newly wealthy elites seized on Fifth Avenue’s open stretches as the perfect canvas for architectural and social ambition. Millionaires erected palatial residences on what had recently been empty ground, turning the avenue into a gallery of private grandeur. The especially famous run of mansions between 59th and 78th Streets gained glittering nicknames—“Millionaires’ Row” and the “Gold Coast”—as one extravagant home after another rose to assert power, taste, and social standing. Although many of these monumental residences were eventually razed as New York modernized, a number survive today, preserved and repurposed as museums, cultural institutions, and nonprofit headquarters. What follows is a look back at Fifth Avenue’s Gilded Age mansions—both those lost to the skyline and those still standing.

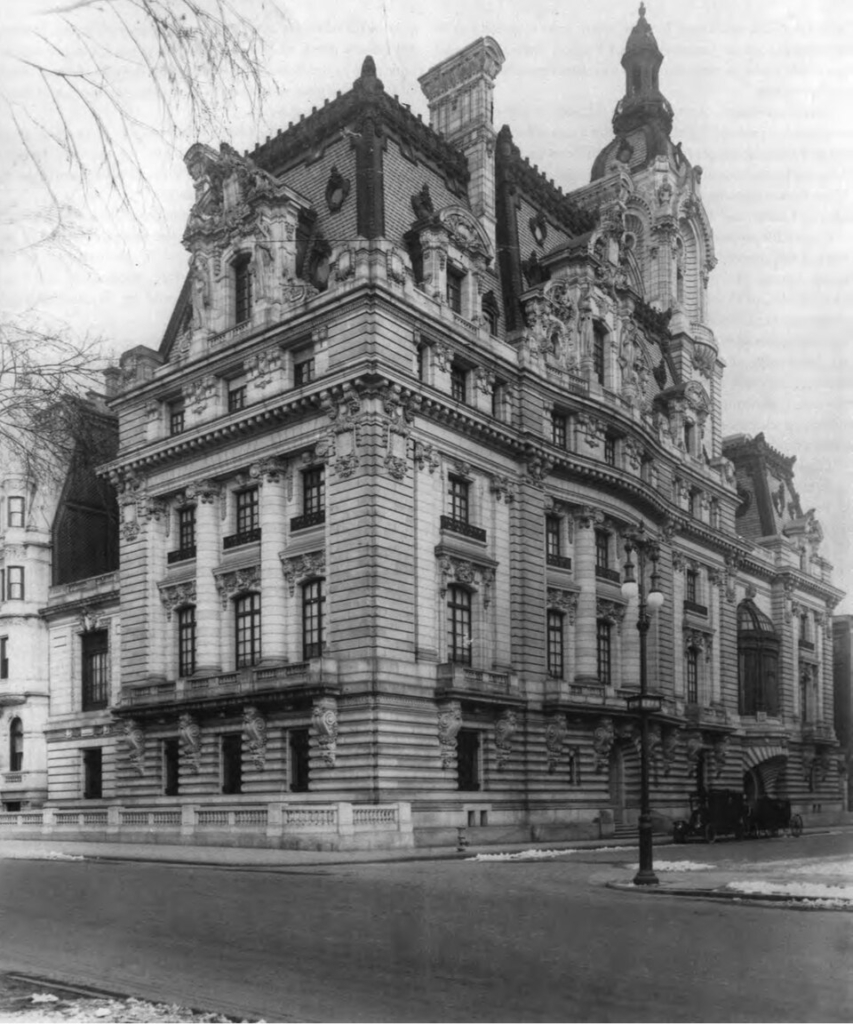

The William K. Vanderbilt Mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue, now demolished, was designed by architect Richard Morris Hunt for William K. Vanderbilt and his formidable wife, Alva. From the beginning, the project was intended to do more than provide a luxurious home; it was engineered to make a statement. Alva wanted a residence that could force open the doors of New York’s highest social circles, and she achieved that breakthrough in spectacular fashion with her 1883 “Fancy Dress Ball.” At a time when she was still viewed as an outsider by the established set led by Mrs. Astor, Alva hosted 1,200 guests—an unmistakable escalation beyond Mrs. Astor’s famed “400.” Mrs. Astor herself was notably absent from the guest list until she made the symbolic move of calling on Alva directly, effectively acknowledging a shifting social order. The interiors of the Vanderbilt home were a carefully curated fantasy of European refinement, from a grand entry hall built with stone quarried in Caen, France, to lavish décor sourced through extensive travel and aggressive collecting. The family reportedly referred to the house as the “Petit Château,” but it did not outlast the era that created it. In 1926, it was demolished and replaced by what became 666 Fifth Avenue.

Mrs. Astor’s first Fifth Avenue home at 34th Street, also demolished, helped set the pattern for elite families moving uptown. The plot was given in 1854 as a wedding gift to William Backhouse Astor Jr. and his bride, Caroline—born Caroline Webster Schermerhorn—by William Backhouse Astor Sr. The original structure was comparatively restrained: a four-bay brownstone that contrasted sharply with the more flamboyant A.T. Stewart mansion across the street. After William Astor Sr.’s death, Caroline became the reigning “Mrs. Astor,” and the townhouse evolved into a social command center. Anticipating larger entertaining duties, she remade interiors with a dramatic flair—transforming a Georgian drawing room into a French Rococo showpiece, commissioning portraits, and adding a ballroom wing that replaced the stables. In that ballroom, she famously held court from a red silk divan—her “throne”—granting or withholding social legitimacy with a glance. Her events were said to accommodate 400 guests, and to be counted among “the 400” was to be admitted to New York’s top tier. Today, the Empire State Building occupies the site.

The William A. Clark Mansion at 960 Fifth Avenue, another lost colossus, represented extravagance at an almost unbelievable scale. Known as “Clark’s Folly,” the home belonged to copper magnate William A. Clark and took fourteen years to complete, finishing in 1911. It was legendary for its sheer size and amenities, reportedly featuring 121 rooms, 31 baths, multiple art galleries, a swimming pool, a concealed garage, and even an underground rail line used to bring in coal for heating. Clark’s construction methods matched his ambition: he acquired a quarry in New Hampshire for stone, created transportation routes to deliver materials, and even secured a bronze foundry to fabricate fittings. Marble arrived from Italy, oak from England’s Sherwood Forest, and architectural elements were sourced from Europe. Yet despite the time and fortune poured into the mansion, Clark enjoyed it for only a short period before his death in 1925. The property was sold, quickly became a burden, and was demolished in 1927. In its place rose a 12-story luxury apartment building designed by Rosario Candela.

The Vanderbilt family’s imprint on Fifth Avenue was so extensive that it became a story unto itself. Among the most famous examples were the “Vanderbilt Triple Palaces,” built in 1882 on an entire block between 51st and 52nd Streets. William Henry Vanderbilt constructed three near-identical brownstones for himself, his wife, and their daughters Emily and Margaret. The homes were designed with entertaining in mind; when hosting large events, the drawing rooms could be opened and combined into one large ballroom, turning the block into a single social machine. The palaces became so admired that Henry Clay Frick reportedly remarked that they represented all he would ever want, a sentiment that foreshadowed his own later Fifth Avenue residence. Over time, legal restrictions on selling Vanderbilt property and art, shifting family needs, and the relentless march of development led to the palaces’ disappearance. The grandeur once contained within those walls has been replaced by the modern skyline and retail storefronts.

Vanderbilt Row extended beyond the triple palaces. Two other Vanderbilt daughters, Florence Adele Vanderbilt Twombly and Eliza Osgood Vanderbilt Webb, received neighboring Fifth Avenue townhouses at 680 and 684, designed by John B. Snook in 1883. Their homes were distinct from the more uniform triple palaces, featuring rusticated stonework, turrets, bow windows, and visually busy rooflines capped with domes and gables. Florence later moved farther north near Central Park, while the Webbs sold their townhouse to John D. Rockefeller in 1913. Both residences were ultimately demolished, their sites folded into the vertical city that replaced so much of Gilded Age Fifth Avenue.

By the early 1900s, wealthy residents increasingly found themselves defending their neighborhood from commercial encroachment. When John Jacob Astor began building the St. Regis Hotel on Fifth Avenue in 1901, nearby homeowners started purchasing additional land in an effort to prevent further commercial development. At the corner of 52nd Street and Fifth Avenue, Morton F. Plant commissioned architect C.P.H. Gilbert to design a substantial stone mansion. The house later became famous for the story—often told as New York legend—that it was traded to Cartier in exchange for a coveted string of pearls. Next door, George W. Vanderbilt built his “Marble Twins,” designed by Hunt & Hunt and completed in 1905, the pair described as free interpretations of Renaissance palazzi. One of those Vanderbilt homes was demolished, but the other remains, still echoing the era’s ambition.

Few Fifth Avenue residences embodied Gilded Age scale quite like the Cornelius Vanderbilt II Mansion at 57th Street, once considered among the largest single-family homes in New York City. Cornelius Vanderbilt II purchased and demolished multiple brownstones on the corner in order to build from scratch, and the result was a monument to inherited fortune and architectural competition. His wife, Alice, ensured the house’s lavishness, commissioning George B. Post for the design and later bringing in Richard Morris Hunt to expand it further in the 1890s. By the 1920s, the mansion was increasingly overshadowed by surrounding commercial buildings and hotels. In 1926, it was sold, demolished, and replaced by Bergdorf Goodman. Even so, pieces of the mansion survived in the city’s fabric, scattered as architectural remnants and decorative fragments in places like Central Park, the Sherry-Netherland Hotel, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Other notable homes followed similar arcs. Jabez A. Bostwick, a founding partner and treasurer of Standard Oil, built a French Second Empire mansion at 800 Fifth Avenue in 1876 and later expanded it for his family. After decades marked by personal tragedy and shifting ownership, the combined mansion properties were eventually demolished to make way for a luxury apartment building. Caroline Astor’s second Fifth Avenue home—built at 65th Street after she fled the encroaching Waldorf Hotel next to her earlier residence—was designed by Richard Morris Hunt and cleverly arranged as two linked living spaces, one for Caroline and one for her son, John Jacob Astor, connected by a vast ballroom sized for 1,200 guests. After Caroline’s death and John Jacob Astor’s tragic end aboard the Titanic, the mansion left the family and was ultimately replaced by Temple Emanu-El.

Not every Gilded Age mansion disappeared. The R. Livingston Beekman House at 854 Fifth Avenue remains a rare example of Fifth Avenue’s smaller-scale grandeur, designed by Warren & Wetmore with a distinctive two-story mansard roof and later designated a landmark. Over time, development rose around it, tightening the space and making the townhouse look even more precious, a surviving artifact pressed between larger apartment buildings. The property later served diplomatic functions and became the site of political tension, underscoring how Fifth Avenue’s buildings often absorbed the changing dramas of the city.

Perhaps the most celebrated survivor is the Henry Clay Frick House at 1 East 70th Street, now the Frick Collection. Frick commissioned Thomas Hastings of Carrère and Hastings in 1912, aiming for a residence that would be tasteful and filled with light, though the final result was undeniably palatial. The house became a vessel for Frick’s renowned art collection and remains one of Fifth Avenue’s most immersive windows into Gilded Age domestic splendor. Nearby, the Edward S. and Mary Stillman Harkness House at 1 East 75th Street offers a subtler expression of wealth—grand in scale, but intentionally designed with smaller, more intimate rooms rather than a single overwhelming ballroom, and distinguished by symbolic ornament and an elaborate fence inspired by historic Italian monuments.

Further north, the Payne Whitney House at 972 Fifth Avenue—designed by Stanford White and now associated with the French Embassy’s cultural services—continues the tradition of Fifth Avenue mansions serving public life. Its interiors, including celebrated reception rooms and the hidden bookstore Albertine, keep the aura of the era alive. The Fletcher-Sinclair Mansion at 2 East 79th Street, later the Ukrainian Institute of America, remains a dramatic French Gothic presence at the edge of Fifth Avenue, offering exhibitions within restored rooms that still carry the texture of the nineteenth century. Other survivors include 991 Fifth Avenue, now home to the Irish American Historical Society; 1014 Fifth Avenue, known as Goethe House; 1048 Fifth Avenue, the former William Starr Miller II mansion that now houses the Neue Galerie; and the Carnegie Mansion at 2 East 91st Street, completed in 1902 and now the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Taken together, these mansions—whether demolished, repurposed, or preserved—tell the story of Fifth Avenue’s rise from a plainly named road to the most famous boulevard in America. The “Gold Coast” era may have faded as the city grew upward and outward, but the remnants of that world still shape New York’s imagination. In the surviving stone façades and converted galleries, you can still sense the ambition that once lined Fifth Avenue, when private homes were built not only to live in, but to be remembered.